Unlocking the Potential of 'Big Data' in Historical Research

Unlocking the Potential of ‘Big Data’ in Historical Research

In this first blog post the team discuss our aims over the next three years, and provide an insight into one of the most exciting aspects of the project for analysing our sources: Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR)

Welcome to the first blog from the team working on the English Merchant Shipping, Trade, and Maritime Communities from the Spanish Armada to the Seven Years War, c.1588–1765 project! Our goal over the next three years is to chart the growth of England’s (later Britain’s) emergence as a global trading nation and maritime power, challenging pre-existing notions of how and why the nation’s maritime empire emerged as it did.

To do this we are focusing on three key research strands: ships, trade, and maritime communities. For ships, we aim to examine and calculate the size (in tonnage and number of vessels), and geographical distribution of the English merchant fleet by undertaking the first systematic, nationwide analysis of the sources over two centuries. For trade, we will demonstrate how England’s overseas and coastal commerce developed by reconstructing the directional flow of England’s seaborne trade from the time of the Armada, when England was a peripheral European power on the edge of Europe, to a global maritime empire by the end of the Seven Years War in 1763. We will highlight fluctuations in patterns of trade, commodities, and routes and highlight key moments of change. Our investigation of maritime communities will examine the English maritime workforce and reconstruct the socio-cultural world of English seafarers and their families. We will study the relationships between different sectors of the maritime community (shipmasters, sailors, and merchants), and how they interacted onshore within their communities.

The pre-modern English merchant fleet (and its labour force) is the best documented of all European states, if not in the entire world. The English customs system was established in the late thirteenth century, where details of ships, merchants, customs, and commodities were recorded for overseas voyages of both English and foreign ships in each region’s principal port (or ‘head port’) along with other major ports in the area for the purposes of taxation. Over time the system was modified and expanded. Elizabeth I’s government implemented a more detailed system for recording trade in government-issued ‘port books’ which, for the first time on a nationwide scale, recorded both overseas and coastal trade (a forthcoming blog will discuss the port books in more detail).

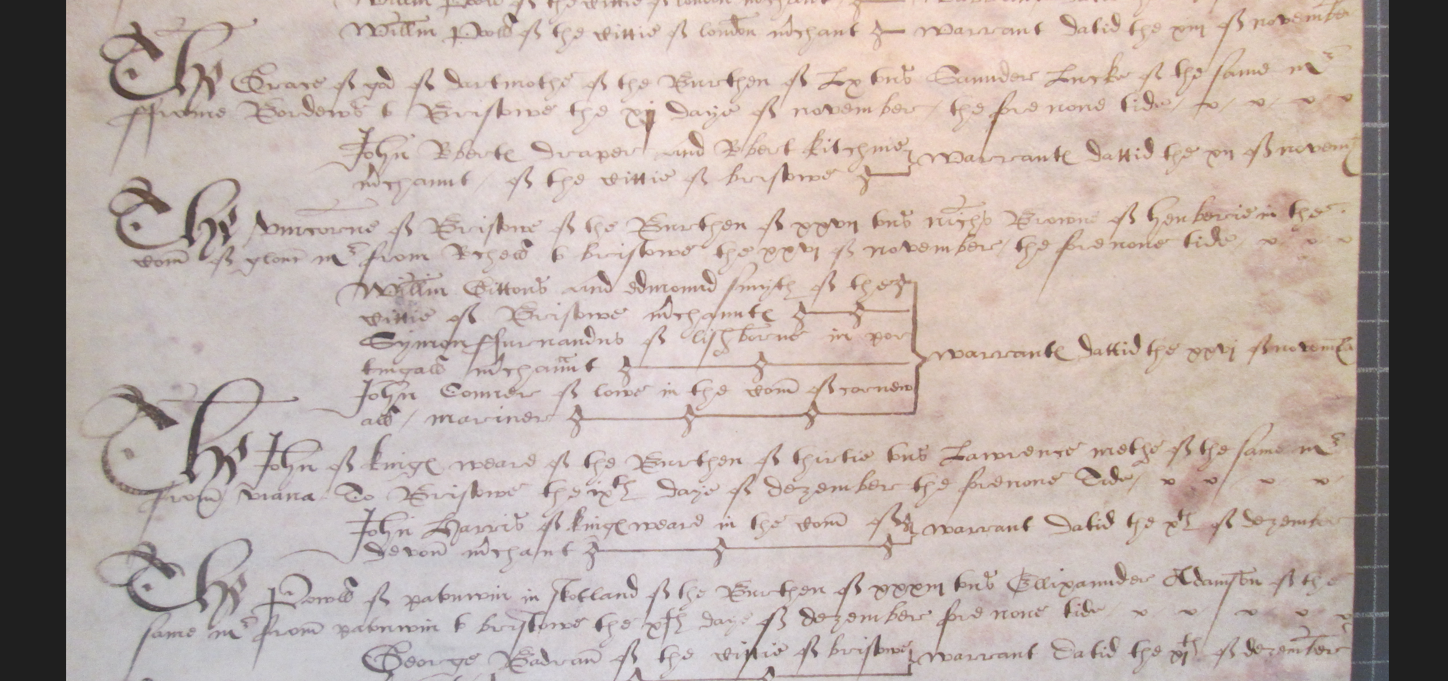

Figure 1 Detail from a Bristol port book showing the names of ships, merchants, shipmasters, commodities, and voyages

The port books run from their introduction at Easter 1565 until the middle of the eighteenth century, and approximately 20,000 survive that cover the period of this project. In each head-port, the customs officials recorded the name of every ship, its home port, the date that it entered or left the harbour, the name of the shipmaster, the cargo carried, the names of the merchants freighting the goods, and the customs duties (or tax) levied on the goods. The port books largely exist in an unbroken sequence, meaning that developments in shipping capacity, trade, and seafarers’ careers can be measured precisely.

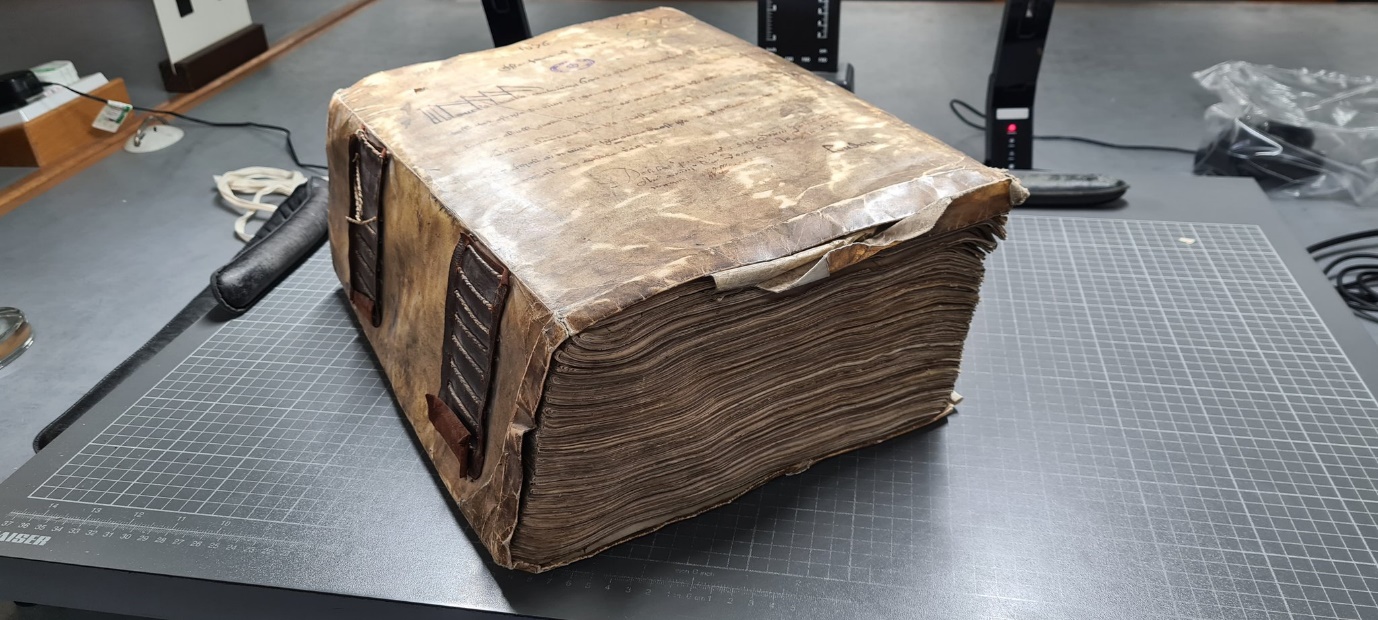

For historians the survival of a large body of source material is most welcome, but it also produces significant challenges. The sheer volume of information contained in one large London port book, for example, means it would take us months if not years to transcribe; in the late seventeenth century many of the accounts for the port run to several hundred folios for just a single branch of trade, such as exports by denizens.

Figure 2 A London port book from the late seventeenth century

To solve this problem, we have linked with Osiris-Ai (www.osiris-ai.com ) who will enable us to automatise the extraction of the data contained in these documents and model it to make the information easier to analyse. With Osiris-Ai, we aim to examine data from c.100,000 digital images to create an open-source database containing thousands of ship voyages from all the nation’s ports, the details of merchants and commodities they shipped, and the names of the ships and shipmasters that operated them, c.1588-c.1765.

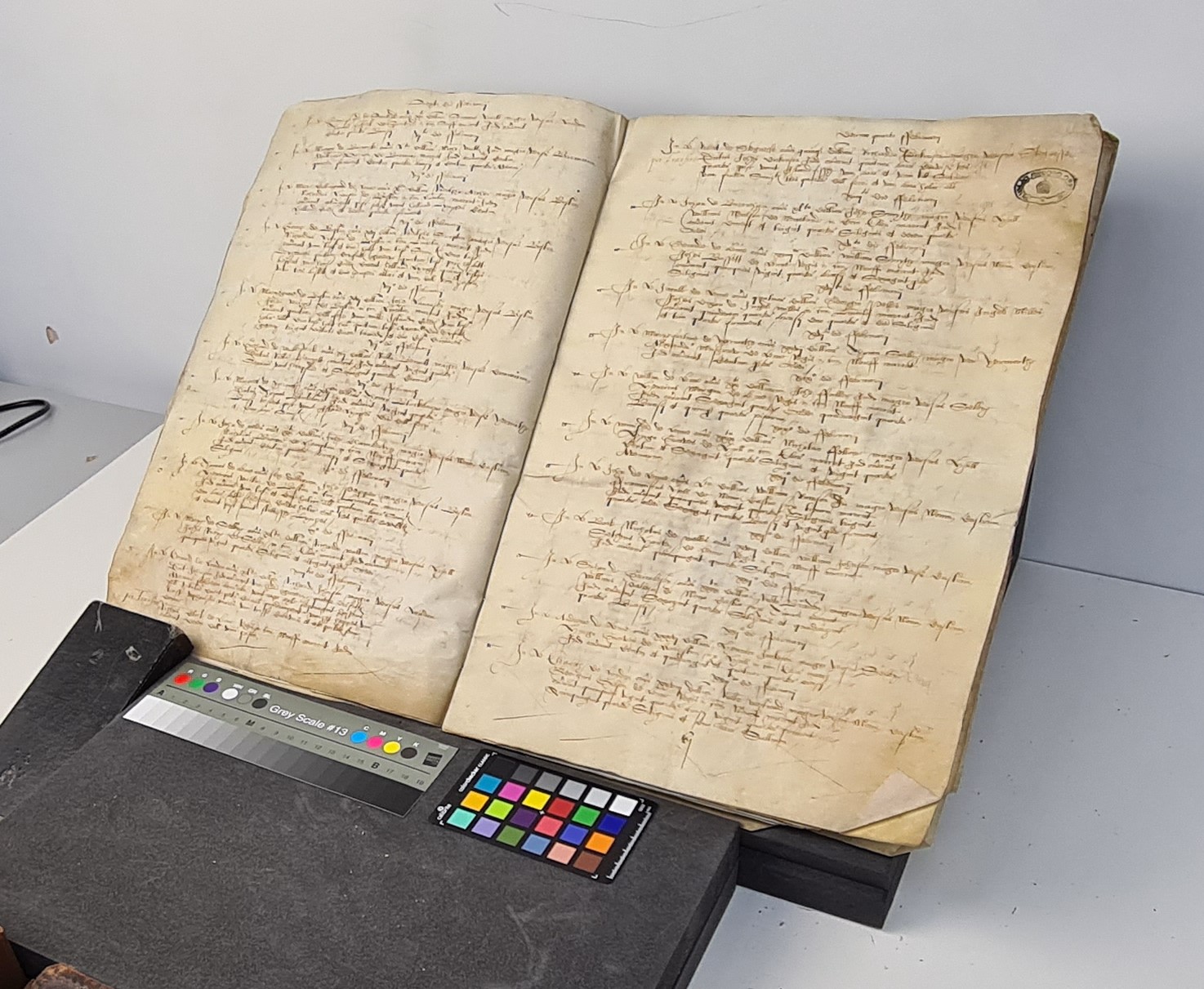

Figure 3 We require a high-resolution digital camera and optimal lighting conditions to record our digital images

To facilitate the use of the computing software and modelling, the images must be taken with high-end photographic equipment which produces crystal clear images of the documents. Once the images are completed, Osiris-Ai trains computers to read the text from these images and learns to understand their structure. The training consists of manually producing accurate transcripts and classification (which we call the ‘ground truth’) and letting the machine (neural networks) infer the most accurate way to obtain the desired text output or document structure from a series of pixels on the image. This is known as machine learning (ML). Once the models have been trained, Osiris-Ai will be able to generate predictions for the transcription and structure of the data contained in the thousands of images we are accumulating. These raw data can then be mapped onto the fields contained in our dataset so that they are easily operable.

Figure 4 One of the port books selected for imaging

A significant amount of groundwork needs to be done before we reach the HTR stage. The key issue is that while the port books largely record the same pieces of information (ship name, home port of the ship, shipmasters’ names etc) they do not do so in the same order. For example, one clerk might start by writing the date of entry or exit of a ship into/out of a port, followed by the name of the ship, the ship’s homeport, and the name of its shipmaster. Other clerks, however, might start each entry by recording the ship’s name, the homeport, the master’s name but place the date of entry or exit of the ship next to the merchants’ names. This means that prior to beginning the HTR process the port books must be read and separated into ‘types’ so that the Osiris can model and sequence the data.

On our previous project, The Evolution of English Shipping Capacity and Shipboard Communities from the Late Middle Ages to Drake’s Circumnavigation, c.1400–1580, we entered the data from the English customs accounts by hand, resulting in a database of c.53,000 shipping voyages (see Medieval and Tudor Ships of England for our previous project and database). However, we only focused on the English ships and voyages, not the merchants and commodities being freighted. With the help of Osiris-AI, we will gather all the information from the port books to produce a dataset which will run into the hundreds of thousands of voyages - a dataset which will be freely searchable on our website at the end of the project – which will contain the entirety of information contained within the port books for both English and foreign vessels.

We look forward to sharing updates on our project over the coming months, so please keep checking our project blog ‘The Crow’s Nest’(Maritime Britain - The Crows Nest). You can also follow us on Twitter (Maritime Britain_AHRC (@maritimebritain) / Twitter), and if you would like to contact the team, you can do so at: maritimebritain@gmail.com. We look forward to hearing from you.