Digital History: A New Method to Analyse Ship Plans

In this latest blog post, Dr Ida Christine Jørgensen, who received her doctorate last year from the University of Portsmouth, has kindly written a guest blog for the project on how digital research methods can be used to analyse ship plans from the eighteenth century

As computer technology forms an increasingly larger part of our work in history and related fields, the scope for digital history expands. Novel tools and methods create new research possibilities and reveal information that was practically inaccessible before. In this blog post, I will present a method of digitally comparing historic ship designs.

From around the late seventeenth century, ship plans (i.e., construction drawings), started to become an integral part of designing a ship in most European navies. Initially these plans were very simple, often with few details on frames and hull shape. During the eighteenth century, however, these plans became increasingly technical. By this point, a sailing ship was an incredibly advanced machine. With trade booming and Europe at war for most of the century, dockyards and their maritime communities were hubs of innovation and technology, buzzing with activity. The race to create the superior fleet was not unlike the space race of the twentieth century.

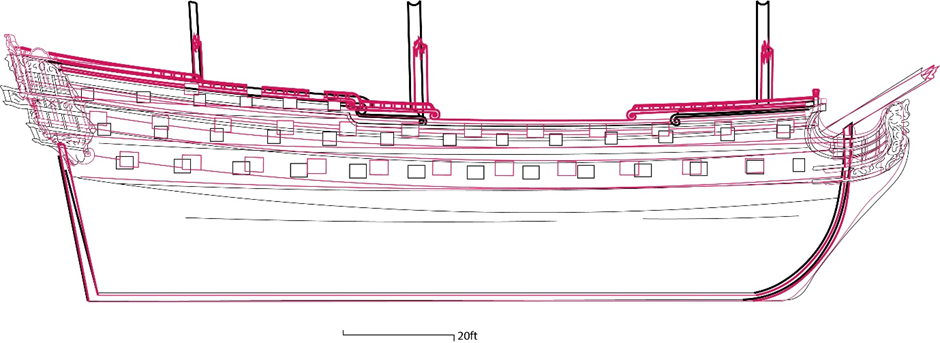

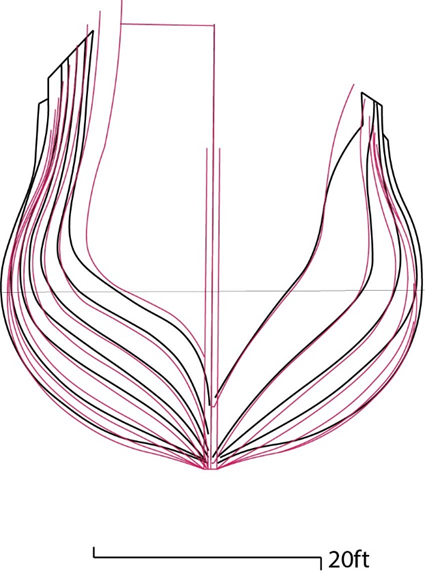

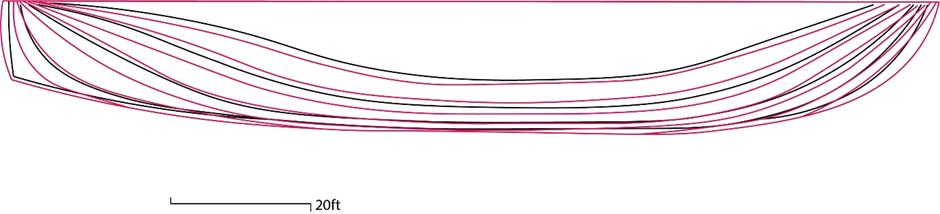

Eighteenth-century ship plans usually consist of three views: the ship in profile, called the sheer plan; the ship as seen from the bow or stern, called body plan; and the ship seen from below, called the half-breadth plan. The sheer plan shows the rake of the stern post, curve of the stem post, and the position of decks, masts, and gun ports. The body plan shows the shape of the hull at various positions throughout the ship. As the hull is symmetrical, half the body plan shows the hull from midships to the bow (right) and the other from midships to the stern (left). The half-breadth plan also shows the shape of the hull, but as sliced lengthways rather than across like the body plan. Again, as the hull is considered symmetrical, only half the plan is necessary, and the other half left out in the interest of making it as clean as possible.

Numerous eighteenth-century ship plans from across Europe are available online through the websites of various national archives. Conducting a digital, comparative analysis of these plans is very simple and can be undertaken with software that is readily available. By digitising the lines of the ship plans in a graphics editor software package, and then scaling and overlaying the plans, the designs become directly comparable. As such, the documents are combined and analysed in pairs to reveal differences and similarities in the designs. Analysing ship design through comparison can reveal more than by studying a single ship plan in isolation. In my research, I have used this method to determine the provenance of certain designs and features. Moreover, the possibilities of this comparative approach are extensive, and not limited to hull design. Comparing the layouts of cabins and holds, for example, may reveal details about how designers sought to optimise space: an important consideration for the crew.

One example of how important a digital approach can be to analysis of ships' plans can be illustrated by a comparison of a Danish warship, Fyen (1745), with the British, Augusta (1736). According to the written sources, the Fyen was heavily inspired by the 60-gun British ship, because a Danish ship constructor had visited the British dockyards and marvelled over it. On his return to Denmark in 1742, he made a similar design, albeit slightly smaller so that the ship could operate in the shallower and narrower Danish waters. The Augusta was considered one of the best ships in the British Navy, and the Fyen enjoyed a similar reputation after her construction. Indeed, her design was later adapted for more Danish warships. The question, however, is how far, and to what extent, did the original Danish ship mirror the British?

A cursory glance at the above diagrams would suggest that there was little between the two vessels in terms of design. Yet the Fyen was not merely a downsized version of the Augusta. In order to make a legible comparison of the lines, the Augusta’s plans have been downscaled but, critically, not by the same factor on each plan. Two of the plans (figures 1 and 3) were scaled down by 12%, while the other (figure 2) was downscaled by 6%. This may seem problematic, but as it is the shape of the hull that this analysis is interested in, the lines overlaying exactly is much more important than length and breadth. In other words, the skill of the Danish design comes from the fact that the designer downscaled the British design but to different degrees as suited the needs of the waters in which the Danish ship was intended to operate: the Fyen being smaller than the Augusta yet downsized differently on various aspects of the design makes the Danish constructor’s work even more impressive.

Taken in isolation, a ship plan provides basic information about the vessel: when and where it was built, its dimensions, and the name of the shipbuilder. But treating the plans wholistically and analysing them in tandem helps us to reveal more information. By looking at the plans like artefacts and ‘reading’ them with an archaeologist’s view, the person(s) behind the plan can be brought to the fore: the constraints they faced, and decisions they made. With this approach, it becomes clear that while eighteenth-century Europe was divided by wars, its navies were very much connected through international shipbuilding knowledge, even though warships were often potent symbols of an individual nation's pride.